By Alina Sivorinovsky Wickham

In early 1999, then 16-year-old Evgeni Plushenko told International Figure Skating,

"Tara Lipinski  was World Champion at 14 and won the Olympics at 15. She's special.

I am just a regular person."

was World Champion at 14 and won the Olympics at 15. She's special.

I am just a regular person."

Not everyone agreed with him. Which was reasonable, as he had already won a World bronze medal. The irony is, Plushenko wasn't even supposed to be at the 1998 World Championships. His coach, Alexei Mishin, ended up taking him to Minneapolis because he had a hunch. When new Olympic Men's Champion Ilia Kulik withdrew, alternate Plushenko got the call.

"I was very surprised," Plushenko remembers.

Suddenly, he found himself pushed in front of dozens of international reporters, all wanting to know who he was and where he'd come from.

"I was so shy then," he admits. "I was timid, uncomfortable, inexperienced. All of my answers were just very brief and to the point."

However, in the almost four years since that first World Championship, Plushenko, now 19, feels he's gotten better at the whole media thing.

"It has to be done," he shrugs. "It's part of the job."

Plushenko's training for his job began at the age of 4 in his home city of Volgograd (then called Stalingrad). Like many of his fellow Russian teammates, he was a sickly child, constantly getting colds, coughs and infections. His mother thought he needed some kind of regular sports training to toughen him up physically, and randomly chose a sport.

A friend of hers had a child skating, so she picked figure skating for her own son. She just had a feeling he would be good at it. Plushenko's father, on the other hand, initially against the entire thing and would have preferred that his boy take up soccer or, at least, hockey.

But figure skating it was. At age 7, Plushenko won his first major local competition, held in the city of Samara. At 11, he came to the attention of Mishin, coach of the 1994 Olympic Men's gold medalist Alexei Urmanov, and moved by himself to St. Petersburg to train.

"I lived for a year without my parents," Plushenko remembers. "I was very, very lonely." No wonder, then that, these days, despite having skated in some of the best facilities all over the world, Plushenko describes his favorite training site as "home."

"Home is where everything is close," he says. "Home is where everything is familiar. I lived without my parents once. I can't live without them again."

Despite homesickness, Plushenko says he took to Mishin from the first day. "It was all so exciting from the start," he says. "My former trainer was never as serious about skating as [Mishin] was. Suddenly, everything about my training changed - new jumps, new techniques, new strategy, new costumes, an entire new attitude."

Armed with that new attitude, three years later a 14-year-old Plushenko won the 1997 World Junior Championship, an experience he exuberantly describes as being, "Colossal! First class!"

The season after he won World Juniors, Plushenko got the chance to direct his singular focus onto his first grownup Grand Prix competition, Skate America in Detroit, where he finished second to 1996 World Champion Todd Eldredge.

"I really wanted to win," he recalls. "But fate wouldn't have it. Still, you learn from your mistakes. I learned in Detroit that Todd Eldredge was beatable. It made me see that all skaters were beatable."

It was that newfound, grownup confidence that helped Plushenko win his bronze medal in Minneapolis.

Mishin summarized the achievement as, "Evgeni had a very quick rise. He went from nothing to being the World Junior Champion. Then he started to grow a little more, and then a little bit more, and we made two very successful new programs, and he got stronger, and his attitude towards training became more serious."

In 1999, Plushenko won the Russian Nationals, upsetting the reigning World Champion, Alexei Yagudin, and the comeback-bound Urmanov.

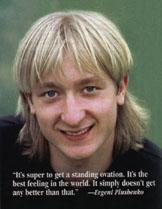

"I expected this," Plushenko said at the time, "because I trained for this." In March of that year, Plushenko also won a silver medal at the World Championships in Helsinki. No longer the shy, timid and inexperienced boy who had faced the world press only a year earlier, he confessed to liking standing at center ice with thousands of people looking at him, because "then all the attention is solely on me. It's super to get a standing ovation. It's the best feeling in the world. It simply doesn't get any better than that. That's why I try to make eye contact with the audience and the judges. To make everyone feel involved in my skating. That's when you really feel that you are getting everybody's attention."

As he took on the 1999-2000 season, Plushenko seemed unstoppable. He won Russian Nationals, the European Championships and the Grand Prix Final.

Mishin professed no surprise with the results. After all, he joked, "We were working to get these same results already last year."

A gold medal at the World Championships in Nice seemed inevitable. But Plushenko crashed and burned in the free skate and wound up in fourth place.

"I think I wanted to win too badly," Plushenko sighs. "I thought just gold medal. I tried too hard and I burned out."

Despite the disappointing results, Plushenko was invited to skate the full Champions on Ice summer tour.

"I don't mind travelling," he says. "I'm getting used to it. I like to see new people, new cities, new arenas, new cultures. It's all very intresting. And I love meeting my fans. The fans are different in different countries. In Japan, for instance, the people are shy and quiet. The fans don't know how to come up and ask you for an autograph or a picture. In America, though, it's the total opposite. The fans know what they want. They scream for more, more. But all countries have great fans, either way."

Indeed Plushenko's fans all over the world had a lot to scream about during the 2000-01 season. After winning every single competition he entered, Plushenko finally reached his goal of a gold medal at the World Championship.

"There were no mistakes this year," he declares proudly.

After his win, Plushenko once again enjoyed Champions on Ice, then, after a month at home in St. Petersburg, spent the summer training in Spain.

Heading into the 2002 Olympic Winter Games, Plushenko intends to train the way he always has: one to two hours on the ice in the morning, followed by off-ice conditioning and endurance training. Then some errands and a break to walk the dog in the afternoon, then two more hours on the ice at night. Periodically, he might attend a class at the university, where history is his favorite subject, or play a few rounds of his favorite non-ice sport, tennis. Otherwise, it's just "skating, skating and more skating."

Is he worried about the Olympics and, especially, about Salt Lake City being at such a high altitude?

"No," he responds. "There is no use in worrying. It has to be done, so it will be. Salt Lake City is just another city. The Olympics are just another competition. I just skate and don't try to make predictions about placing.

"I did that in 1998 and in 1999 - I really, really, really wanted to win. But now I know it's all in God's hands."

тнрнюкэанл : пегскэрюрш : яяшкйх

рбнпвеярбн онйкнммхйнб

тнпсл : цняребюъ