By Alexandra Stevenson

"I think I was born to be a figure skater. I think it was fate I thank God for letting it happen."

"I think I was born to be a figure skater. I think it was fate I thank God for letting it happen."

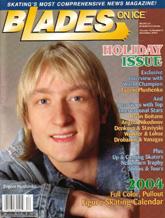

The reigning world champion, Evgeni Plushenko, has seen it all. He's gone from - if not from rags, then at least from an unpretentious, modest background - to a world of luxury. He jets around the world, always welcome by adoring fans, coping with overwhelming demands on his time. "You can't say yes to everything but I try to do my best for my fans," he says with a wry smile, obviously enjoying himself.

He is at the peak of his technical ability, a blond Adonis with the face and flawless pink and white complexion of a mischievous cherub painted by Rubens. He's a whirling dervish, a lion whose attention-getting roar is his incredible ability to stay vertical while spinning and jumping to a blur on a steel blade barely a quarter of an inch wide while gliding over the oh-so-slippery ice.

He is in New York, in Madison Square Garden, for his first competition of the new season, a cream puff contest sponsored by Campbell's Soups, the International Figure Skating Classics, an ABC television special.

The event includes the world's best singles. Whether Plushenko finishes first or last will not affect his substantial amount of appearance money, nor his ranking in the coming season. He is proud and he is looking forward to challenging, and potentially overshadowing fellow Russian Alexei Yagudin. "He is a super rival. I try to surpass him. It spurs me on."

Yagudin was more guarded in his view of their contests. Earlier he said, "Life would have been much easier for us if we didn't exist at the same age". The last time the two competed was in this contest in Daytona Beach, October 5, 2002 when Yagudin came out ahead.

It was Plushenko's only loss of the 2003 season.

Plushenko is ready for a rematch but cautions, "I want to win. I am hurting but I will still try my best. This is my job."

Although media wary, Plushenko has gradually come to realize that speaking to the press is an important part of catering to the fans. He is working on his English, and Western journalists are beginning to warn to him. He even talks about doing an autobiography and dismisses the fact that it's a little soon - he has not yet turned 21. "I have lots to tell."

Does he get tired of everyone asking the same, and often inane, questions? "Everyone wants to know what I think during my performance. I think nothing. Before I skate I just go through the program and then I go on the ice and do everything. I feel the music. All my movements come from inside."

Does he get energy from the crowd? "I don't know how it is for others because I've asked other guys and they said. "Applause or not, I concentrate on myself and that's all.

"But I see everything. I hear everything. And it's pleasing when the fans, the audience applaud. They help me. Then I begin to dance with them. I get energy from them and I want to skate well for them. It's not fun without them. I feel the Americans like me more and more each time I tour."

Is he always "up"? "There are times when sometimes I simply cannot skate. Then I leave the practice. In such cases, I try to relax. I shower, go to sleep or try to switch over to something else. The psychology means a lot in sport. It's very important, and what the coach said to you."

The Campbell's competition provided only one 40-minute official practice session to get used to the arena. Plushenko stays on the ice for half that time leaving before his music played.

"The problem is an injury - a torn meniscus of the right knee," explains his coach Alexei Mishin, who has guided Plushenko since he was 11 years-old, transforming the small, unsophisticated backwoods urchin into a suave 5'10" accomplished, worldly sophisticate. "He wrenched it while he was in Japan giving an exhibition at the end of August. He was completely off the ice for two weeks. It is worrying." Plushenko seems unconcerned. "We have good doctors in Russia. They will heal me."

The Russian way of coaching involves a greater closeness between pupil and teacher then in the west. Mishin is invariably present when Plushenko skates. Today he sits moodily staring out at the empty 18.000 seats waiting for his protege to change into street clothes after the practice. He is having a mid-life crisis.

"You know I skated here in 1969," Mishin explains. "I was the World silver medallist. (He and his pair partner Tamara Moskvina, representing the old Soviet Union, beat the legendary Oleg and Ludmila Protopopov but were pipped for gold by the newcomers, Alexei Ulanov and Irina Rodnina.)

"The Worlds were in Colorado Springs and Madison Square Garden was one of the stops on the tour for the medal winners. I remember it well. It was the last season we competed. We became teachers - 34 years - such a long time ago! It was a different world. I feel old."

Mishin is 62 and one of the most famous coaches in the world. He should be relaxing, enjoying Plushenko's success and the fame and travel opportunities this affords him.

He is confident Plushenko is the best skater in the world. "Technically, everybody has seen he is the best jumper in the world. No question. His spins are unmatched, he has new moves and he has grace enough to loan some to the other competitors." But he worries. "I am not sure what to think of the (new) system. I understand the International Skating Union wants to get rid of the possibility of the judges" intrigue, colluding, making deals┘ but the computer picking the judges and averaging the marks is like mashed potatoes, running all together.

"In Oberstdorf the standard of the skaters was not the best and the test was not 100% a true result. It is difficult to tell exactly how this new system will work under other circumstances.

Plushenko seems unfazed by the situation. He says he accepts whatever the ISU decides. After all, what can he do about it? The ISU sets the rules. "It's going to be hard for all the skaters. Mishin and I have been working on my spins, the Biellmann, the Bagel and new spins. And we know that if you do the jumps later in the program you get a bonus. My triple Axel, Lutz and flip will be after that point."

Plushenko was the first to land a quad-triple-triple in competition. "I love to jump." No one has yet landed a quad Lutz in competition, and Plushenko hopes to be the first. "I have landed quad Lutzes and quad Salchows in practice but lately because of my injuries, I cannot practice them. I want to show them as soon as I can. Any sport is dangerous and I have my share of injuries. I will go back to them."

In New York Plushenko presented the St. Petersburg Centennial, with which he won the 2003 world title, in his usual - that is to say unusual-outfit, black, white and silver with one black glove and one white glove. Although he too-footed the landing of his first quad toe loop, he accomplished a second one. His showing brought a standing ovation from the over 9,713 spectators.

None of his main competitors, the world silver and bronze medalists, American Tim Goebel and Japan's Takishi Honda, and three time U.S. champion, Michael Weiss, were able to land a quad.

Goebel, who first competed against Plushenko six and-a-half years ago, has yet to bear the Russian. He has not forgotten their first battle. "I knew he would be a grate skater. You don't forget the great ones," Goebel said with a laugh.

Plushenko said he expected to unveil his new routines for this season at Skate Canada. All he would reveal is that the short program is a flamenco and the long is new, unusual, and innovative - a tribute to famous Russian ballet master Vaslav Nijinsky.

Mishin emphasizes that picking the music has been of paramount concern. "The high level of emotions the music gives to the skater is a friend of the technical component. It helps create the energy needed for the toughest elements. For Zhenya (Plushenko's nickname) it's 'I feel the music' or 'I don't feel'. If he doesn't, it's a stop! We must keep searching."

Plushenko has learned to roll with life's punches. Just as he was beginning to accumulate some savings with his prize and exhibition money, Russia devalued its currency and the money he had banked lost much of its value.

After his win in Washington D.C., he was invited to throw out the ceremonial first pitch for the Baltimore Orioles. He good naturedly agreed but then was terrified because he didn't want to embarrass his hosts. He knew it was an honor but had no idea what they expected from him.

"This was new for me. I'm happy they invite me but I never have watched this game in my life. I watch hockey, soccer, tennis, but what is this baseball?"

For those into astrology - he isn't - Plushenko's a Scorpio, born on November 3, 1982 in the hamlet of Solnechni (which means "sunny" in Russian) in the cold Khabarovsk region of Siberia. That is in the far east of the former Soviet Union, only 500 miles as the crow flies from Japan's northern island of Hokkaido.

His father, Victor, was working on the construction of BAM, the Bajkal-Amur-Magistral railway. He and his wife, Tatiana, and daughter, Elena, were living in a wooden temporary trailer. It was an inauspicious start for someone who would become a major star in an elitist sport and gain fans around the world all before his 21st birthday.

For those into astrology - he isn't - Plushenko's a Scorpio, born on November 3, 1982 in the hamlet of Solnechni (which means "sunny" in Russian) in the cold Khabarovsk region of Siberia. That is in the far east of the former Soviet Union, only 500 miles as the crow flies from Japan's northern island of Hokkaido.

His father, Victor, was working on the construction of BAM, the Bajkal-Amur-Magistral railway. He and his wife, Tatiana, and daughter, Elena, were living in a wooden temporary trailer. It was an inauspicious start for someone who would become a major star in an elitist sport and gain fans around the world all before his 21st birthday.

Neither parent had any sort of sporting background and, at first, it appeared Plushenko would never head in that direction. He was a sickly child and at one point he survived double pneumonia.

Plushenko has never revisited his birthplace, although one day he would like to. "It is too far - 10 hours by plane from were I live, St. Petersburg, and than a long train trip, maybe as long as the plane ride." When he was three, the family moved to Volgograd, a city in the south of Russia, east of the Ukrainian border. A year later a chance encounter was to change his life.

Mother Tatiana was walking Zhenya through a park, giving him his daily exercise, when she ran into an annoyed acquaintance dragging her daughter who was crying because she didn't want to skate. The acquaintance asked Zhenya if he would like to skate and when he said, "Yes", she promptly gave the girl's skates to his mother. Rather surprised by this unexpected windfall, Tatiana and Zhenya proceeded to a frozen pond.

Zhenya did not have to be encouraged to try out the skates and it looked like he had fun. "I was totally fascinated by it." The acquaintance later suggested Tatiana take him to the Palais des Sport where he could get skating lessons.

A few months later Piushenko took part in his first competition finishing seventh out of 15 - not bad considering that dome of his rivals had taken classes for a year and-a-half.

Many years later his mother laughed at this turn of events. She told Russian television, "I was very happy he had somewhere to use up his energy. He was a very active child. He couldn't sit still and was always where he shouldn't be. When he came home from training, he was tired. We were very happy about that."

His first coach was Mikhail Makaveyev, a Master of Sport in weight lifting who had organized a figure skating school. Now there's an unusual combination! Plushenko explained, "He was an excellent coach for physical preparation and off-ice training to help with the jumps."

At age seven Plushenko won his first competition. "I wanted to win. People began to say maybe this could be a future champion."

Later he was to become famous as the only man to do the Biellmann spin which requites extreme flexibility. He and his mother saw Denise Biellmann, the 1981 World champion, doing her trademark spin on television in which she yanks her skate over her head so it obscures her view of the ceiling. He decided he wanted to try it.

"It was an amazing move, pure magic. So everyday my mom worked helping me stretch into that position. I would lie on the couch and try and pull my leg up. I am very proud of it. I still do it but, from doing quads all the time, I'm getting some nagging injuries - groin, back, knee. Because of that the Biellmann is more painful now."

His budding career nearly came to a complete stop in 1994. After the Soviet Union broke up, the flow of government money into many state sponsored activities was reduced and his rink was converted into an automobile dealership's showcase. The skaters had only a month's notice that this avenue was to be closed. "When I stopped training, I completely lost interest in the surrounding world. My mom tried to make me play soccer or learn karate and I even agreed at first but quickly pulled out."

Makaveyev got a well-known skating judge to ask Mishin to audition the 11 year-old. Mishin said, "He was quite a gift. I am very thankful he came to me. It was immediately obvious that the boy had talent. Within two minutes I could tell but, of course, I didn't tell him that."

It was a great coup for Plushenko to be accepted by Mishin but he had to move to St. Petersburg about 1,000 miles to the north. At first his mother could only stay with him briefly and he stayed in a dormitory, a very unpleasant time.

"It was hard. I had to find out at a very young age things that no one needs to find out. Everything was a problem because of money." Fending for himself was not easy. "I never ate enough and went to sleep hungry very often. I missed my mom's cooking - borsht, pelmeni, chicken and potatoes."

Mishin says that wasn't necessarily a bad thing. "A hard childhood is a stimulus. It makes a person (hungrier), more willing to fight for what he wants. When he came to me he was beginning to grow. But the difficulties of growth passed and the diamond shone as it was supposed to."

Some of his classmates made fun of Plushenko for practicing a "girls" sport. "I fought sometimes. I had to prove them wrong. I proved with my fists that it wasn't true."

At the Jubilee rink he was on the ice with other Mishin pupils, and the stars of his sport, Urmanov and Yagudin. "At first Urmanov and Yagudin found it funny to have this little kid training with them. I learned a lot from Urmanov. I watched him all the time. It's a great feeling to be on the ice with an Olympic champion "Everyone asks if Yagudin (who is nearly three years older) and I are enemies. We're not fighting. We fight on the ice but we talk like normal people in real life, even though we're not friends.

"When I first moved to Petersburg, he immediately considered me an opponent and that reflected in our daily lives. We traveled abroad together but I always felt he was somehow against me. But it was good to have someone to compete against everyday. He would push me and I would push him to do more."

Much later Mishin was asked to compare these three. "Every great diamond is unique," is all he would say. Mishin, whom Yagudin was later to criticize as too much of a disciplinarian, undertook to guide Plushenko in both on and off the ice activities. "Mishin was like a second father, like Professor Higgins. He taught me how to behave in public."

After a year Plushenko's mother was able to join him in St.Petersburg and got a job shoveling asphalt in the streets. They rented one room in another family's apartment. "It was terrible," Plushenko explains, "but I am trying to forget this time in my life now."

There were some good times. Soon after he came to St.Petersburg, he met his idol, Victor Petrenko, who had won the 1992 Olympic gold medal.

"First time I saw Petrenko was when I was 11. He was in St.Petersburg for the Goodwill Games. I got his autograph.

"Then in four years, I met him at a (made for television) competition, where I beat him accidentally. I felt so embarrassed in front of my idol, but he came up to me and comforted me, saying, "Zhenya, everything happens in sport. You are younger than me. I am already a veteran."

Plushenko returned Petrenko's friendship by donating his time, as have many other skating stars, to appear as a guest in Petrenko's October 4 Viktory for Kids benefit show. The yearly show, this time in Danbury, solicits money for children from the atomic disaster area of Chernobyl in Petrenko's native Ukraine.

Part of Plushenko's early training in St.Petersburg involved a dance class with a choreographer from the Maryinski Theater Ballet. She thought him talented enough to pursue a career in that area. "My mom told me I had to chose." In hindsight, obviously he made the right decision.

Plushenko worked and learned, and advanced. "I had all the triples from toe loop to Axel when I came to Mishin but there was no technique, no right execution, there was only my natural ability to jump high. That was Mishin who made me a world champion. He's the best coach, not just for me but the best coach in the world." Plushenko landed his first quad when he was 13.

In his first international event - the 1996 World Junior Championship, which actually took place in November 1995 in Brisbane, Australia, he finished sixth. He had only been out of Russia once before, to Paris accompanying Mishin who gave a seminar there, and he was thrilled to go half way round the world.

"I remember going swimming in the ocean. It was warm and wonderful but I wouldn't go far into the water. I kept looking around, looking for the sharks. I was terrified."

The following year he gained his first international victory in the Blue Swards contest in Chemnitz, Germany. Shortly afterwards, in Seoul, Korea he was crowned World Junior Champion.

The following year he gained his first international victory in the Blue Swards contest in Chemnitz, Germany. Shortly afterwards, in Seoul, Korea he was crowned World Junior Champion.

In his first entry in the European championship in 1998 in Milan he helped Russia sweep the medal in the men's event. He took silver, Yagudin won and Alexander Abt was third.

Plushenko was pleased with his showing: "I did the combination quad toe loop-triple toe loop for the first time in competition. It was not clean, but I didn't expect to skate so well in my first Europeans".

The Olympic in Nagano, Japan was a few weeks afterwards. A new rule since amended had been devised the number of skaters a country was allowed to enter into the Olympic Games. Russia and Plushenko were its victims.

As with the current system points are given for the competitors' finish in the previous years' World Championships, and the scores determines whether one, two or three entries are permitted.

Urmanov had been forced to pull out of the 1997 World Championships after leading going into the long because he injured his groin in the worm-up, and that, unfairly, counted as if he had not qualified for the final.

So, although Yagudin had finished third and Kulik fifth in those Worlds, only two Russian men were to skate in Nagano. Plushenko would have gone if there had been third place. "I watch the Olympics on television of course, but it was hard, I wanted to be there".

Kulik won gold; Mishin is still upset about Yagudin's behavior in Nagano. "He was wet. He had just come out of the shower with wet hair and sat down under a fan. I told him to move, but he wouldn't listen. Katya (Gordeeva) told him too, and Arthur (Dmitriev). So look what happened - he got flu, very high temperature! It affected his skating, and he finished only fifth. He wouldn't listen. But Zhenya, Zhenya listens". It was at this point that Mishin lived up to his reputation as a very savvy coach.

Suspecting currently that Kulik might not continue the 1998 World Championships, Mishin brought Plushenko along with Yagudin to Minneapolis "just in case" The authorities wouldn't let Plushenko practice on the championships ice, but they were able to practice in another rink. The 15 year-old had recovered from jet leg, was rested and familiar with American City when Kulik citing a pinched nerve in his back, finally acknowledged at the last possible he wouldn't skate. Kulik subsequently ended his eligible having never won Worlds, saying that with the Olympic gold he didn't need any other titles. Mishin explained:" There were some politics at play there".

Yagudin won his first Worlds in Minneapolis, but complained that Mishin was favoring Plushenko. Shortly afterwards. Yagidin left St.Petersburg and Mishin to begin training in Connecticut with Tatiana Tarasova. Although he won four world titles and Olympic gold, Yagudin has never won the Russian national championships. In Minneapolis Plushenko took the bronze with Todd Eldredge the second. He received an invitation for the Champions on Ice tour, a wonderful opportunity to see the United States and earn considerable money.

That summer Plushenko gained another bronze in the Goodwill Games in New-York despite being forced to wear back brace. In the fall he took the second place in Skate America. A knowledgeable skating aficionado clearly remembers the lasting impression he made in that event. " We were all talking about the boy in green. We knew he was going places".

The next week he won Skate Canada and then claimed victory in the NHK Trophy in Japan where he gained his first 6.0 shortly after his 16th birthday. Holds the record for the youngest male to earn that ultimate accolade in international competition. His total of 6.0 has now reached 38.

The following year (1999) he was second again in the European Championships to Yagudin, but advanced his world ranking one notch to second (behind Yagudin). Later that year he won his first nationals, a title he has held for four consecutive years.

Yagudin won the short program in the 2000 Europeans in Vienna but Plushenko advanced his career by dethroning him and taking the title. Plushenko went into Worlds in Nice in the south of France with high gold medal hopes. But this sunny Mediterranean city was unlucky for him.

He took second place behind Yagudin in the short but had a terrible free skate and dropped to fourth overall. "I felt great stress. I was overwhelmed with a desire to win and be first. But if you think about victory, about what the judges might do, it becomes a very strong obstacle. It distracts from the right spirit."

"I heaped reproaches on myself. "Why did you do that? Why didn't you execute that jump? You should have won." I worked hard, I practice a lot. In training everything goes okay but why do I fail in competition?" "Now everything has changed. I said: "Zhenya, you're so young. You have plenty of time. Just practice to your heart's content". "I don't even discuss winning wit my coach. I compete with myself and only then with others. I try not to think about marks, the first place or gold medal. The most important thing is to show what you are capable of on ice. The rest will come on its own."

Another coach might have called in a psychologist. But not Mishin who says: " If a skater needs a psychologist, there nothing good. At least, I don't see anything good."

Plushenko rebounded from his disappointment with a vengeance. In 2001 he successfully defended his European title, beating Yagudin both short and long programs, to claim his first world title.

In Vancouver at that event, Plushenko not only delighted the judges, he pleased spectators by taking his coach's advise and doing a different long program in the qualifying round to that in the final.

It was there that he unveiled his most famous exhibition for which he wore a full body suit, which made him looks, as if he were a nearly necked wrestler with huge muscles. "I like to play with the audience, get them on my side. That program was very well received. Sex Bomb was my coach's idea. It was fun and many people laughed so I'm happy for that. All of a sudden I was called a sex symbol in figure skating. It's funny. I definitely don't have any pretence to that."

The success buoyed his hopes off success in Salt Lake but a worrisome injury kept him out of the European championships and he became the fifth reigning men's world champion to do into the Games and failed to win gold.

The men's contest was the first figure skating event after the pairs contest and it was completely overshadowed by medal frenzy surrounding the judging scandal, a great shame because it was very good event. Unfortunately for Plushenko, he faulted the most important of the eight required elements in the short program. "After the third revolution, I opened up and didn't do the quad toe loop-triple toe loop combination. I was very upset. I was only fourth and I'm not used to being in fourth place. Support from my coach and friends helped me a lot. Everyone kept saying that I should just skate because I know that everything will be fine. Overall I was able to be the second and I'm happy about that. In the long I did a quad-triple-triple for the first time in the competition and I also did a triple Axel - half loop - triple flip. But, because of the high altitude, there was so difficult to skate, I have never experienced anywhere else. I have both good and bad memories of the Olympics - good that I could skate in the Games, bad- that I didn't skate clean. After the free I got very sick and didn't skate for seven days. Before the exhibition I trained for only half an hour. When I came on the ice, I was in a very bad shape and I fell in the exhibition". Afterwards he was so exhausted; he didn't defend his world title in Japan.

However, last season Plushenko was unbeaten everywhere except of the minor Daytona Beach TV contest His win on October, 3 in the Campbell's contest brought his tally of gold medals to 34. Since 1996 in 57 competitions he has only failed in eight, and only one of those was in the last four seasons. So, where does he keep all those gold medals? "I have a big stuffed elephant at home - four-and-a-half feet tall. He has his own special chair. I put them all round his neck".

Plushenko's earnings have allowed him to buy a home in St.Peterburg. He provides support for his whole family, which includes his sister's little daughter Dasha, who is 7. "She doesn't skate but she is very good at school. She shines in English, Spanish and Russian. She is promising tennis player" The new addition to the family is a bulldog named Golden.

He has no plans to leave Russia for the USA like many of his countrymen have. "Conditions at the Jubilee rink have improved. They were very bad at one point- it was very-very cold, there was no place to warm-up, the ice was only rarely resurfaced. But all that has changed. The facilities are as good as any in the West". He has earned his diploma from the Lesgaft Academy. "They give you five marks. It was like waiting for the skating scores".

Amazingly his parents do not travel abroad to watch him compete. "This has been tradition since I was kid and I don't want to change it now", says Plushenko, who admits that he is superstitious. "Isn't everyone? Aren't you?"

He always wears a golden cross around his neck presented him by his godfather, and a maroon string around his wrist, which was given him by a friend as a memento of a bad car crash they both survived in Madrid.

Other coaches have tried to poach him away from Mishin, thought he won't say who. "Very often this has happened. American and Russian coaches promised me a lot of money, but I feel good with my own coach. I didn't need anyone else". He does intend to keep competing till 2010. "I'm young. But it's a sport and I'm not a robot, I'm not a machine like the Terminator. I'm normal. What wares me is that after all those victories don't see me as a human anymore. They forget I have a heart beating in my chest- not an engine. There's blood in my veins - not oil; I know pain and fatigue. I can lose."

He always wears a golden cross around his neck presented him by his godfather, and a maroon string around his wrist, which was given him by a friend as a memento of a bad car crash they both survived in Madrid.

Other coaches have tried to poach him away from Mishin, thought he won't say who. "Very often this has happened. American and Russian coaches promised me a lot of money, but I feel good with my own coach. I didn't need anyone else". He does intend to keep competing till 2010. "I'm young. But it's a sport and I'm not a robot, I'm not a machine like the Terminator. I'm normal. What wares me is that after all those victories don't see me as a human anymore. They forget I have a heart beating in my chest- not an engine. There's blood in my veins - not oil; I know pain and fatigue. I can lose."

But one second after that somber statement, the enthusiasm floods back and his blue eyes twinkle. "I will win everything. I need this Olympic title, but it doesn't change your life if you don't win the Olympics. It is not the end of the world. I will still skate for audiences. My main competitor will be myself."

Plushenko is very proud of his home city. The music he used for his program in Washington, D.C. and for the Campbell's October 3 International was composed to commemorate the 300th anniversary of St. Petersburg. He also organized and hosted a skating event in June in St. Petersburg celebrating this grant occasion. Recently, he appeared in a television commercial, along with a tennis star, for lollypops, which have become hugely popular in Russia. "I enjoyed it but just for this short time, we filmed from 9 a.m. till midnight!" The experience has whetted his appetite. "I would like to shoot a movie. Perhaps act out some big shot racing around in a motorcycle with a gun in his pocket - some sort of Robin Hood of the 21st Century. I would also like to open my business - a restaurant or a disco club. Right now I really don't have the time for that although I've got some interesting offers from business people".

And how would he sum up his current life? "I think I have fame, I have money, even though it's not so much. My parents love me. I would like more health, though".

And what about romance? "I don't talk about that," he says. Many in the entertainment feel it is wise for someone dependent on the adoration of women fans to maintain an eligible behavior status. This summer, however, he and a young lady called Yuliana, spent time in Sochi, a resort on the Black Sea, before vacationing in Turkey.

And what does Mishin think? The often-somber looking Russian bear brightens up. "Not all world champions go into figure skating history, but Plushenko will. You will see."

тнрнюкэанл : пегскэрюрш : яяшкйх

рбнпвеярбн онйкнммхйнб

тнпсл : цняребюъ